SPECIAL

Argentina Animation Day

NOVEMBER 9- 4:00 PM (GMT-3)

PRESENTS

RESCUE PROJECT OF ARGENTINE ANIMATED CINEMA | MAFALDA FOR EXPORT | QUIRINO CRISTIANI AND OTHERS

THE AUDIOVISUAL SCREENINGS PRESENTED BY THE MUSEUM OF CINEMA WILL BE AVAILABLE UNTIL NOVEMBER 20TH

Rescue Project of Argentine Animated Cinema (Selection)

By Andrés Levinson

For some time now, we have been working on the rescue, preservation, and access of animated films made in Argentina during the 20th century. Some of these films were more well-known at the time than others, with some creators producing relatively extensive works and earning a prominent place in the field of animation, while others made only a few films with limited circulation. However, in most cases, these films are now almost entirely forgotten or unknown, especially to the younger generations. The aim of this project has been to bring them back to life, so to speak, not because we are dealing with masterpieces—though some certainly deserve that label—but because they are part of the history of Argentine cinema, and we believe it is always good and interesting to be familiar with the works that preceded us in the field we are currently engaged in. Additionally, and perhaps this is the only truly important aspect, there is an aesthetic pleasure in each of these films that makes it worthwhile to retrieve them from the storage vaults where they have been kept for so many years.

The selected shorts, with the exception of Víctor Iturralde and Luis Bras’s films (provided by Fernando M. Peña), are part of the Buenos Aires Museum of Cinema’s archive. The chronological order (which will not be strictly followed) suggests starting with Adventures of Julián Centeya, the work of Juan Oliva, a Catalan-born artist initially trained by Quirino Cristiani. In the 1930s, Oliva worked as a cartoonist for various print media, including the magazine Cine Argentino by Antonio Ángel Díaz, where he created the character Pepito Celuloide, a comic strip based on cinema themes. Julián Centeya was produced by the newsreel Sucesos Argentinos, owned by Díaz, for the “Filmoteca Argentina” series. Its release took place sometime between late 1940 and 1941 at the Astor and Porteño cinemas. Unfortunately, the film’s soundtrack by Leopoldo Sciamarella has been lost. Centeya is part of the rich gaucho tradition that, particularly in comics, Oliva began to define with El Gaucho Rendija, a comic strip with similar style and humor. Like Rendija, Centeya suffers the vicissitudes of a gaucho in the modern city, a classic theme of Creole humor.

The three short films by José Burone Bruché, two of which feature his character Contreras and one featuring the clown Pamplino, were recently rescued in digital versions from 16mm prints. Burone Bruché worked as an illustrator for various print media such as El Hogar and La Novela Semanal during the 1930s and 1940s while also developing advertising comics. In 1942, he was called by EMELCO studios to replace Juan Oliva in directing the company’s animated film division. There, he created two significant series: the first, Los Consejos del Viejo Vizcacha, now lost, where he adapted stanzas from José Hernández’s Martín Fierro; and the second, Animated Proverbs, produced in 1947, which were recovered by the Museum of Cinema for this project.

In 1948, he founded his own production company, América, with the support of SINCCA Films, along with his core team, Pablo J. Leiva, scriptwriter and chief filming technician, and Francisco Blanco, set designer. Together, they created the film The Discovery of America, also lost, and a series of shorts between 1951 and 1952, featuring two moderately successful characters: Contreras, the man who always contradicts everything, and the clown Pamplino. If there was ever a character in Argentine cinema who was notoriously difficult, it was Contreras. It’s not necessary to elaborate on his main characteristic, already evident in his name, but it’s safe to say that El Contra, a successful television character created by Juan Carlos Calabró in the 1980s, would seem mild in comparison if we placed them side by side.

Bruché’s drawing style, like Oliva’s, was initially classical and anthropomorphic, in the tradition established by Walt Disney, which influenced much of that generation of artists. However, that classicism began to shift, particularly with more twisted creations like Contreras, toward the realm of adult comic strips, where Bruché seemed much more at ease and inspired than when he was constrained by the conventionalism required by the animated proverbs characters created for CINEPA.

In the following decades, a series of filmmakers emerged who deliberately moved away from traditional drawing and even from the camera as a tool for animation.

Frequently associated with the remarkable filmmaker Norman McLaren, Luis Bras and Víctor Iturralde Rúa experimented with the technique of direct or camera-less filmmaking, without initially being aware of the Canadian’s work. Both developed a series of surprising shorts by drawing or scratching directly on the surface of the film material. Bras expanded the boundaries of what was possible for reduced formats like Super 8 to such an extent that it’s difficult to describe the nearly obsessive work involved in creating films like Toc-Toc or The Thief of Colors, conceptual, abstract, and beautiful works. Iturralde, on the other hand, drew with fluidity and technical precision a series of luminous and occasionally colorful landscapes that seem to flow from frame to frame, constructing and deconstructing small worlds in a matter of seconds. Perfectly articulated, they can tell a story or discard it with the same spontaneity. From Bras, we will see perhaps his most celebrated film, Bongo Rock (1969), scratched on 35mm film, while from Iturralde, we will see Petrolita (1958), also his most well-known work, and Duerme Liebrecita (1956), a beautiful color fable recently rediscovered by Fernando M. Peña. In this same line of work, we include La Cumparsita by the Tucuman filmmaker Bernardo Vides Almonacid, a remarkable animated choreography set to the eternal tango by Rodríguez Matos.

Simón Feldman was one of the most important directors of the Generation of the 60s, the group of young filmmakers who renewed Argentine cinema at the beginning of that decade. Los de la Mesa Diez (1960) was his most important film. Throughout his career, he occasionally but very interestedly devoted himself to animated filmmaking, experimenting with various techniques. The feature film Los Cuatro Secretos (1976) and the short films Happy End (1982), El Zorro y los Presumidos (1975), and Caraballo Mató un Gallo (1983) share the technique of cut-out animation, animated frame by frame. We will have the opportunity to see El Zorro y los Presumidos, a little-known film made possible with the support of the National Endowment for the Arts.

Within the same technique, and almost secret, are the shorts by Rodolfo de Luca, which seem to anticipate the popular character Zamba, widely known from Argentine public television in recent years. De Luca created a character, Perico, who, like Zamba, participates in various key episodes of Argentine history. In this case, he accompanies Martín Miguel de Güemes in defending Buenos Aires during the English invasions. This is intriguing, among other reasons, because this is not the most well-known aspect of Güemes’ military career. Later, Perico joins José de San Martín in the campaign for Peru.

Lastly, El Día del Caramelo (1976) by Héctor “Kalondi” Compaired, also made for the National Endowment for the Arts, is one of those small masterpieces that, for some unknown reason, remain out of sight. Kalondi was an architect, cartoonist, and graphic humorist, one of the very good ones in Argentina during the 1960s. He published in Primera Plana, 4 Patas, Tía Vicenta, and Satiricón, among others. He died young in 1998. El Día del Caramelo reveals a diversity of drawing and animation techniques; it is a true visual collage, which also displays his acidic yet refined humor. Comparable to the excellent short film Compacto Cupé by Catú (Jorge Martín), a contemporary of his, it diverges from absurdity to precisely highlight the dissonances of the world we inhabit.

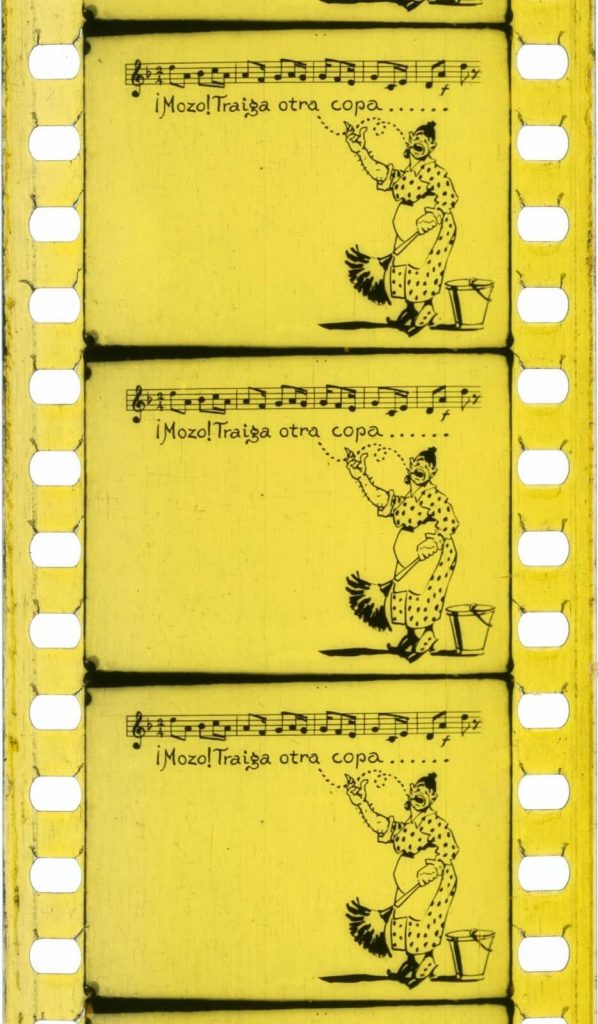

He holds a degree in History from the University of Buenos Aires (UBA) and is currently a PhD candidate in History at the same university under the supervision of David Oubiña. He is currently in charge of the Research and Curatorial Projects area of the film archive at the Buenos Aires Museum of Cinema. A specialist in the history of silent cinema, as well as in the preservation and archiving of audiovisual media, he teaches Argentine History at UBA and History of Documentary Cinema in the postgraduate program at the National University of Tres de Febrero. He has also taught History of Cinema at the Universidad del Cine (FUC) and at New York University. He has curated retrospective exhibitions, documentary films, and film cycles at various festivals and exhibitions. He has participated in numerous conferences and published articles in journals and books. He is the author of the book Cine en el país del viento: cine mudo en la Patagonia Argentina.

He is a researcher specializing in film and mass media, a documentary filmmaker, a social communicator, and a cultural manager. He is the author of Breve Historia del Dibujo Animado en Argentina (A Brief History of Animated Drawing in Argentina), the only book dedicated to the history of local animated cinema. Along with Alejandra Portela, he authored Un Diccionario de Films Argentinos (A Dictionary of Argentine Films), which, with three volumes and one in preparation, is an agile and in-depth survey of feature film production and a frequent reference on Wikipedia. He co-authored with Raquel Quintana the volume Afiches del Peronismo (Posters of Peronism). In the book Ideas Materiales, Arte y Diseño en los 60s (Material Ideas: Art and Design in the 60s), he wrote the chapter dedicated to Advertising and Graphic Design. In 2015, he joined the Museo del Cine Pablo C. Ducros Hicken, researching historical advertising and animation archives, and curated, among other things, the exhibition 101 Años de Animación Argentina (101 Years of Argentine Animation) and various cycles at BAFICI and Mar del Plata. Previously, he was in charge of the film department at the Centro Cultural Rojas/UBA, where he programmed cycles and courses. With three decades of experience in advertising agencies such as Ogilvy and McCann, and with national and international awards, he directed the independent feature film Picsa, a documentary. He also directed an exhibition on Ingmar Bergman’s presence in Argentina as part of the Mar del Plata Film Festival. As an educator, he has taught courses at ENERC, UNTREF, UBA, HBO Olé, and Warner Channel, among others. A pioneer in the democratization of information on social networks, he manages the Facebook fan page Historia de la Publicidad (History of Advertising), which has 18,000 followers.

Tribute to Quino: Mafalda for Export

Tribute to Quino: Mafalda for Export

A Mafalda movie? The idea intrigued Quino as it was a way to take his characters into a different, less routine setting. Mafalda had transitioned from the daily comic strip in the newspaper El Mundo to the magazine Siete Días Ilustrados, where the demand was for a weekly page consisting of four strips. By then, Mafalda was already a global celebrity, and since Quino was friends with Catú, he was attracted by the proposal from producer Daniel Mallo to make a feature film. This was in 1971. The condition was to base the scripts on a selection of the already published strips. The company was named Producciones Azúcar, comprising Mallo, Catú, Oscar Desplats, Ricardo Rovira, and Norberto Gaite. Soon, a talented team, including Naum Spoliansky, José Zalnero, Miguel and Silvia Nanni, Roberto García, Luis Cedrés, Rafael Rodríguez, Néstor Pichel, and Dante Pettenón, was fully engaged in the project.

However, coordination became a significant issue. After months of work and over half an hour of produced material, it was concluded that they were dealing with a collection of disconnected gags. Consequently, they decided to shift focus and create a television series instead of a feature film, partnering with Panamericana Televisión.

The idea was pitched to Héctor Ricardo García of Teleonce (now TELEFE), who had previously attempted, without success, to bring Mafalda to his newspaper Crónica. In 1973, when the comic strip had stopped being published and democracy was returning to Argentina, El Mundo de Mafalda aired twice a day with moderate success and some indifference. However, the initial goal of selling the product abroad was achieved, with the shorts being distributed in several countries. In total, more than two hundred strips were produced. As part of this international expansion, in 1974, a new voice dubbing was done in Mexico, replacing the voices of Rina Morán, Pelusa Suero, and others. Over the years, the partnership dissolved, and Mallo became the owner of the material, to which he later added separators and presented it as a feature film, with the nominal direction of Carlos Márquez and a new Argentine dubbing. But that is another story.

The shorts presented by the Museo del Cine at BIT BANG were produced to offer the series to channels in various Spanish-speaking countries. The 35mm positive material comes from Oscar Desplats’ donation to the Museo del Cine and includes the original voices of the series.

Quirino Cristiani & others

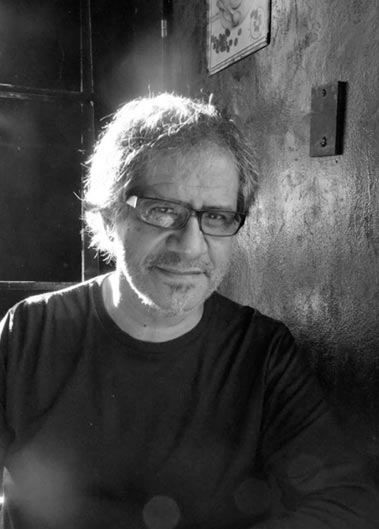

He went down in history for having created the world’s first animated feature film, El Apóstol (1917), which parodied President Yrigoyen, but his legacy goes beyond that anecdote. Today, almost nothing of his work has been preserved, except for a few shorts made for the Film Revista Valle newsreel and the film El Mono Relojero from 1938. In the former, his original technique and style can still be appreciated. Andrés Ducaud (Una Noche de Gala en el Colón, 1918) and Romeo Borgini (Del Puerto de Palos al Plata, 1926) were his contemporaries and learned alongside him, as did many young artists later on.

Compilado Quirino Cristiani y otros (Fotogramas)

Argentina, 192-? Director: Quirino Cristiani / Luís Moglia Barth, otros.

Duración: 15 min.

Procedencia: Museo del Fin del Mundo, Tierra del Fuego / Filmoteca Buenos Aires

Preservación Fotoquímica y Restauración Digital: Museo del Cine de Buenos Aires.

SCREENING AND DIRECTOR’S PRESENTATION: MONDAY, NOVEMBER 9 | 4:15 PM

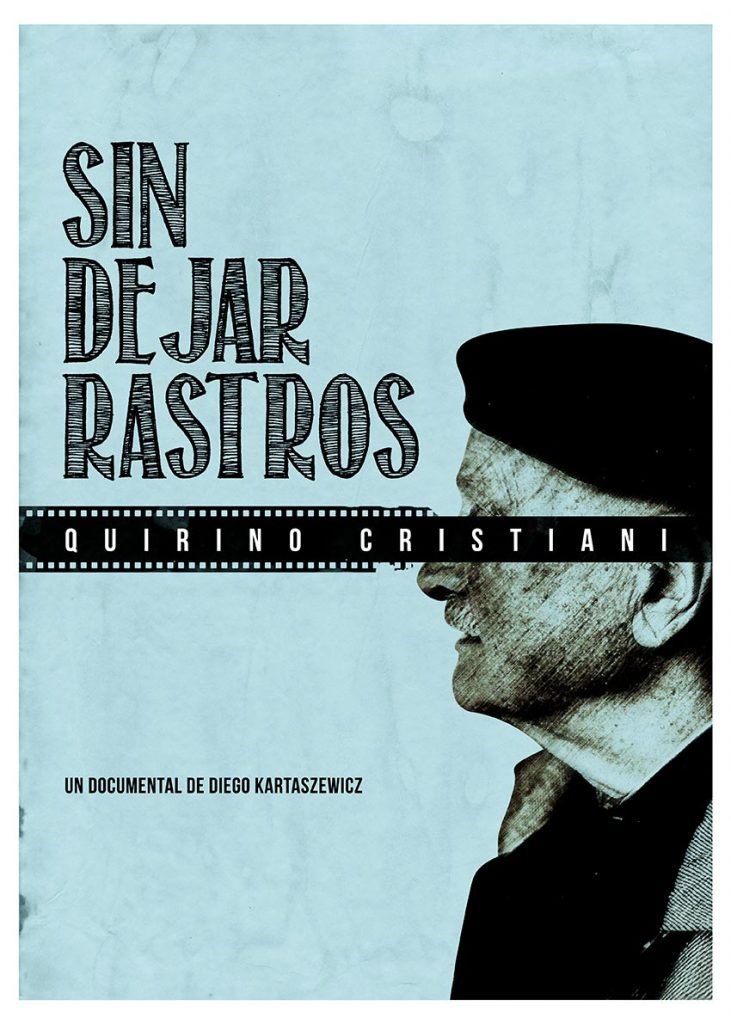

Sin dejar rastros

Sin dejar rastros portrays the life and work of filmmaker Quirino Cristiani (1896-1984), an Italian-Argentine animator, cartoonist, and comic artist, who created the world’s first animated feature film, El Apóstol (1917).

Much of his work was lost in various fires, with only a short film titled El Mono Relojero (1938) surviving. His grandson, Héctor Cristiani, along with a team of animators, seeks to rescue him from obscurity with a small and humble tribute, animating original pieces from the first sound animated feature film, Peludópolis (1931).

- Director and Screenwriter: Diego Kartaszewicz

- Duration: 67 minutes

- Genre: Documentary

Interviewees: Manuel García Ferré, Giannalberto Bendazzi, Cesar Da Col, Oscar Mario Desplats, María de los Ángeles De Cecco, Héctor Cristiani, Raúl Manrupe, Natacha Mell, Norberto Galasso, Oscar Vázquez Lucio (Siulnas), Marcelo Niño, Marilyn Lazzarini, Bollo Quintana, Eduardo Fernández, Alejandro R. González, Graciela Cristiani De Cecco, Marcela Cassinelli, Luis Bernardi, Silvia Nanni, María Valdez.

MASTERCLASS: MONDAY, NOVEMBER 9 | 8:00 PM

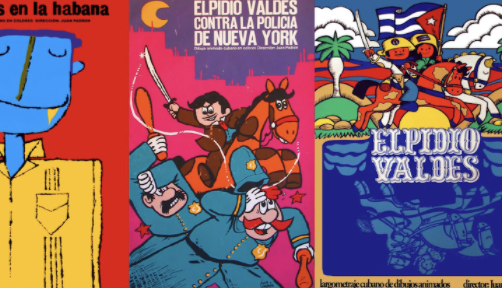

Despacito: A Quick Look at Latin American Animation

The history of animation in Latin America mirrors the story of a fragmented continent striving to understand itself. Unlike the development of animation in the United States, which centered around technological advances, intellectual properties, and patents, animation in Latin American countries served as a tool for expressing the needs of oppressed artists living in ever-changing political landscapes. This necessity is reflected in the fragmented aesthetics, the empirical passion for learning, and the underlying violence present in many of these films. Come and take a look at this mosaic, and perhaps you’ll discover why animation might be the most fitting medium for this historical moment.

Animator and creative director, he studied Visual Arts in Bogotá, Animation in Cuba, and earned his Master’s degree in the United States. He is currently the creative director at Titmouse Animation Studios and the founder of Amaltea INC. Simón has worked for the Japanese TV network TBS and has directed projects for clients including HBO, the Gates Foundation, Netflix, Disney TV, Starburns Industries, Apple, and Adult Swim. Recently, he served as the animation director for Dua Lipa’s video Hallucinate and created animation for Charlie Kaufman’s latest film. His filmography has been showcased worldwide, including seven consecutive selections at the Annecy Animation Festival. He has received various accolades, including a double award at the Adobe Design Achievement Awards, two Annie Award nominations, and two semifinalist nominations for the Student Academy Awards. In 2011, he was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship for artists.